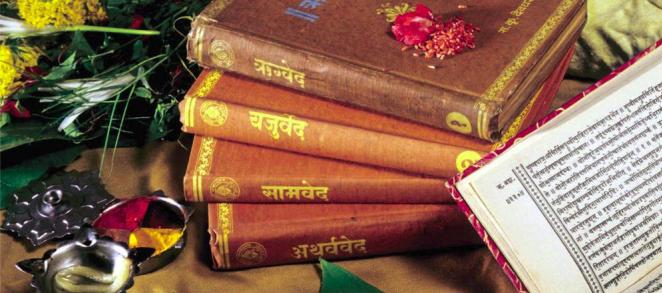

The foundations of all Dharma stems from the Vedas, whether these Dharmas purport to uphold, follow or oppose the ideas of the Vedas. As we understand it today there are 4 Vedas: Rg, Yajur, Sama, and Atharva. The Rg Veda is composed of approximately 10,600 verses divided into 10 Mandalas (literally “circles” but meant as books). These verses are broken down into 1,028 mantras or hymns and are in poetic form. They are focused on the praise of Devas, Asuras, Nature and it’s personifications and other beings, forces or ideas. The Yajur Veda is about 1,875 verses in prose format and is focused on the liturgical and ritualistic practices related to the Rg Veda particularly in regards to yagnas or fire sacrifices. The Yajur Veda tells you how to use the mantras in the Rg Veda in a sacrificial and worshippable setting. The Sama Veda is almost entirely the same as the Rg Veda but set to melodic and chanting form. The Atharva Veda is the last of the four Vedas and relates mostly with everyday practices, rituals, hymns, and magic mantras. It is a mix of poetic and prose hymns. Most of the daily and common practices such as upanaayana, naming, marriage, and death rites are found in this text. Atharva maybe a cognate with the word for holy fire, Atar, in the Zend Avesta, the pre-Zoroastrian text. There are numerous theories that connect the pre-Zoroastrian people and religion with the Atharva Veda.

Generally speaking the modern “religion” of Hinduism and all its branches view the Vedas as being the source of all its knowledge and authority. Buddhism and Jainism do not accept the Vedas as authority. While this is the general understanding of the relationship between the Vedas and Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism, it is a bit more complex than that. I will delve into the complexity a bit more in the podcasts. In this post I want to really spend some time with the Vedas overall, if I’m being honest I think this focus will spill over a few different blogs and the reason for that is that the Vedas are layered, in fact, they are multilayered. What I mean by that is that they have multiple means to interpret them, understand them, relate to them and experience them.

Sanskrit is a very bountiful language, words have a variety of meanings depending on its context, many times you can read the same sentence in multiple ways. A word that will pop up frequently is Dharma and it’s slippery, while it literally means “that which upholds” from the root dhr “which holds, maintains or uplifts” but it also means religion, righteousness, way of life, essential essence of a thing, law, nature, duty, custom, laws of nature, laws of morality, morality itself, rituals, order, and a numerous other definitions. In addition to words like Dharma, we have to contend with how to interpret the Vedas, is it literal, symbolic, esoteric, philosophically, liturgically, mythologically, poetical license or something else or a mix of the above or all of the above.

The Vedas are not like any other text we have in human existence currently. They have been preserved almost exactly the same for over 5000 years, by this I mean the words, the way they are chanted, the intonations, the cadence and so on. It is one of the most unique instances of human transmission without change and this was all done via oral transmission until about the first few centuries in the common-era when it was finally written down consistently. Even after they were written down, the numerous schools known as Shaakhaas continued the oral transmission. Each Shaakhaa is linked to a particular Samhita and the associated texts, branches, and treatises. No other people or civilization we currently know of has maintained their vast texts in such consistent and unchanged format. When I first learned sanskrit I didn’t really understand that concept of intonation but as I’ve studied more, it is apparent to me that one cannot hope to really understand and appreciate the Vedas without having a grasp of the intonation and accents because the Vedas were never intended to be “texts” as we understand it but rather are uniquely and explicitly an oral tradition. They are meant to be chanted and sung with proper tones and accents, it is the power of the word made into sound, not into writing.

The Vedas, which are broken down into the Samhitas, Brahmanas, Aranyakas and Upanishads, are the oldest Indo-European texts we have (there is a bit of scholarly contention if the Indo-Aryan language of the Hittites, who are referred to in the Hebrew Bible, are older, my own view is that the language of the Hittites are much later than Vedic Sanskrit, for a variety of reasons including Hittite doesn’t have any demarcation between genders and the numerals show linguistic change over time that maybe Sanskrit hasn’t undergone.). The divisions between Samhita, Brahmanas, Aranyakas and Upanishads are not always perfectly clean, rather there is some bleeding over from each to the other. Here is the break-down of the Vedas:

- Samhitas: These are the oldest layers of the Vedas, which include mantras, hymns, prayers, liturgy, poetry and worship. (Samhita means Sam “together” and Hita “put” so literally that which is brought together or put together). This is what we would consider being the most proper layer of the Vedas.

- Brahmanas: These are the parts of the Vedas that are concerned with the rituals, how do you use the hymns, prayers and poetry in a ritual. They are also commentaries on the Samhitas.

- Aranyakas: These are connected to the Brahmanas, in that they relate to the rituals but the Aranyakas are more philosophical in nature, what is the purpose of the hymn or ritual. (Aranyaka means Aranya “forest” and Ka “who, which or what”, that which concerns/related to the forest, meaning the ideas that stem from those thinkers who reside in nature and away from the cities, there is an undercurrent to these thinkers in which the life of contemplation and living away from the cities or population centers was of vital importance.)

- Upanishads: These are the texts that most people refer to when they say Vedas. The Upanishads are the ultimate, esoteric and spiritual philosophical truth and meaning behind all the other sections of the Vedas, that is why they are called Vedanta or Veda and Anta (Anta: meaning the end of or goal of), the goal of Vedas. The Upanishads literally means: Upa “close/by/near” Ni “down/below” and Shat “to sit”; To sit below and learn. They are called thus because the student literally sat next to and below the teacher as the teacher taught. It wasn’t a simple rote exercise but a dialogue and even a dialectic between the teacher and student (I use dialectic here in the Hegelian sense of thesis, antithesis and synthesis, the teacher would present one view, then some objecting views and then a final view that incorporated both).

The Vedas are not simply a single perspective and they aren’t purely theistic, they are varied and open. The poets and the seers of the Vedas are grappling with a variety of issues: nature, life, love, philosophy, war, survival, cohesion and so on. They come from different schools of thought, ideas and influences so by nature they aren’t homogenous, they are varied and diverse much like how they viewed reality. Therefore, the Vedas reflect a number of different views but with an underlying sense of unity. Scholars for years have argued that the Vedas present a variety of perspectives polytheism, monotheism, monism, henotheism, pantheism, panentheism and others. A case in point is the wonderful Nasadiya Sukta (Na-Asat: Not the Un-reality sukta). It starts with the idea that neither Sat (Being) nor Asat (Non-Being) existed then eventually that One came into being by its own tapas (austerity/power) then creation issues forth then the entire Sukta ends asking a fascinating question:

From when all creation had its beginning,

Maybe it Formed Itself or Maybe it Did Not,

Even He who sees it from the Highest Realm,

Only He knows or maybe He does not know even…

There is a germ of true speculation here and a germ of hidden truth. The seer of this Sukta which was in the 10th Mandala of the Rg Veda is trying to drive home the experience of being connected to the moment of creation yet not being able to explain it. At the time of creation, nothing nor anything existed neither was there life or death then the ONE came into being on its own. It is beautiful and yet beyond words to understand. It is when words and concepts cannot add any value, like how do you talk about before time or vision before the idea of shade or color. We live in a world where concepts are tied fundamentality to experience to speak of one recalls the other. The Rishi of the Sukta here is telling us that there is something beyond our conception that happened and is happening but we are lost to know it or to describe it, it can only be experienced.

This is a very basic and general understanding of the Vedas, over the next few blogs and podcasts, we will cover the rich mythology of the Vedas and the key important ideas that the Vedas convey. Aside from the above pure Vedic corpus, there are thousands if not tens of thousands of unique and individual texts which add to, explain or expound upon the Vedas.

The Vedas are known as Shruti or “that which is heard” implying that the knowledge or wisdom of these texts was “heard” from the deepest vibrations of reality. The Vedic composers or seers were known as Rishis, the etymology of the word is diverse and contested some think its root is from drs which means to see, others derive it from rsh which means to flow (Monier-Williams defines rishi as Rsati jnaanem Samsara parah or the one who reaches beyond the universe with spiritual knowledge). Whatever the actual etymology is, the Rishi is one who has experienced the truth and conveys it. The Vedas are also considered Apaurasheya or not from beings, they are considered eternal and beyond the universe, meaning the truths they expound and the vibrations of the sounds to be beyond this existence. They are not the divine revelation in the Judeo-Christian-Islamic sense, they aren’t from God but are co-eternal and part of God, they are a reality that is glimpsed by the Rishis, sometimes in bits and pieces and other times in totality. (A book that does a great job in introducing and explaining some of the concepts in the Vedas is A Vedic Experience: Mantra Manjari by Raimundo Panikkar, a Jesuit Priest who delved deep into the Vedas to try and understand it. He stated, “I left Europe (for India) as a Christian, I discovered that I was a Hindu and returned as a Buddhist without ever ceasing to be a Christian”. This is one of the purposes of this entire endeavor to spread the ancient and perennial knowledge of the Indic world so as to help people embrace diversity and the experience of existence.)

All the other texts that are not the Vedas fall under the term Smriti, or that which is remembered. These texts are the ancient knowledge, wisdom acquired, experience, lessons, traditions, history, and lore that has been passed down over time. They are considered secondary in authority to the Vedas, these texts must be interpreted or viewed in the light of the Vedas, as the Vedas are considered paramount. Smriti texts include the various Puranas (hundreds), Itihasa (Mahabharata and Ramayana), all the various shastras, all the sutras, tantras and anything else. All this to say that knowledge was of vital importance in the entire Indic framework, this makes sense when you consider that the term Veda itself means “to know” very similar and a cognate of the word video from the Latin videre which means “to see”. So Veda in this sense means “to know” with the mind (maybe a sort of sight like videre) and also “to know” as in to have heard, both of which connect to a direct experience.

Most of what most if not all Hindus practice and believe today stems from the Smritis, the actual knowledge or practice of the Vedas is extremely limited and even when the Vedas are invoked most people refer to the Upanishads. If all this seems tough and inscrutable then you aren’t alone. We have to remember there are thousands of years of history and tradition behind all this but it is not all ad hoc, there is a rhyme and rhythm to this all with strong foundations. Yet we should not think everything is beyond questioning or reproach, we need to employ our reason, logic, experience, and morality in assessing it all. Some things will be needed to be seen as belonging to a cultural and temporal milieu, others will need to be contended with for moral considerations or irrationality but a lot of it is timeless, complex, relevant, sublime and vitally important to both our human existence and more universally to understanding and experiencing reality.

Over the next few blogs and podcasts, we will cover topics related to the Vedas and the ideas/concepts that are of Vedic significance.

Quick Aside:

My main area of knowledge is the Mahabharata, Itihasas, Puranas, Upanishads, and Philosophy, I am not an expert in the above but I believe I am rather competent with over 20 years of study. My Sanskrit is also a bit rusty so I use a lot of secondary sources and the Monier-Williams and Apte dictionary a lot so I may make mistakes, so please correct me and forgive me. My interest in starting this entire endeavor has also pushed me to start reading more of the Vedas directly and using other studies to understand it, as such I am learning as I read and again my interpretations may be faulty so I am open and enthusiastically request everyone to correct me or give me your thoughts, but I think generally I am on pretty strong footing. The Vedas are a very ancient, dense and difficult group of texts, experts spend a lifetime trying to learn it and understand them, I am standing the shoulders of those giants and trying my best to grow in that knowledge. Thanks!

+ There are no comments

Add yours